Prevention, fixing general practice, improving access and spending wisely. There you go. Simples.

We’re getting older and sicker and the healthcare system as it is now can’t cope with it, says the Grattan Institute.

The think tank today released its Orange Book 2025, detailing policy priorities for any incoming federal government.

“Six in every 10 Australians now have a chronic disease, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or dementia,” said the report.

“Each year, we lose an estimated 4.4 million years of healthy life to chronic conditions. This accounts for 85% of Australia’s total disease burden.”

The Grattan has detailed a four-pronged plan it says the government should follow to ensure the healthcare system is fit for purpose going forward.

“Important foundations have already been laid,” it said.

“Money has been set aside for an Australian Centre for Disease Control (ACDC), which can help prevent chronic disease.

“Early steps have been made to reform general practice funding and workforce models, to support the sector and make chronic disease management easier. And experiments have shown how gaps in rural access to primary care can be overcome.

“In this coming term, the government must build on this foundation, moving from commitments, planning, and experimentation to systemic reform.”

Prevent chronic diseases

The Grattan described Australia’s preventive policies as “piddling”.

“We’re leaving big potential health gains on the table.”

Part of that is due to a lack of spending, the report says. Peer OECD countries – Canada, the UK, Italy and Finland – spend at least double what we do on prevention.

But also, even when a prevention model has been proven to work, Australia has not instituted it.

“These include a tax on sugary drinks (a policy adopted in most countries around the world), mandatory salt limits for manufactured foods, mandatory front-of-pack nutrition labels, and restrictions on junk food advertising,” said the Grattan.

“Powerful vested interests, such as the ultra-processed food industry, actively work to block reform. Strong institutional guardrails can help overcome these reform blockers. Providing those guardrails should be a central role for the ACDC.

“The role and independence of the ACDC should be legislated.”

The institute called for the government to strike a “national prevention funding deal” with the states, increasing investment in prevention, but only for initiatives supported by strong evidence and that the ACDC endorses as “good value”.

Support GPs to manage chronic disease

According to the institute, Australians are more likely to end up in hospital for conditions that are potentially avoidable through primary care, compared to other wealthy nations.

“Broad, multidisciplinary primary care teams are the best way to help patients manage chronic disease,” said the report.

“But GPs in Australia are less likely to work in teams than their peers in many other countries.”

PHNs should be better funded to expand multidisciplinary teams in under-served areas and to help clinics successfully integrate new workforce groups.

“Australia’s outdated way of funding GP clinics must change too,” said the Grattan.

“As well as blocking multidisciplinary care, it penalises clinics with poorer and sicker patients, making it hard for the GPs in those clinics to spend enough time with the patients who need care the most.”

Switching from a fee-for-service to a new, opt-in funding model that is “fairer and more flexible”.

Related

“Most of the funding should be patient budgets that reflect each patient’s need,” said the Grattan.

“New practice payments to promote bulk billing could be expanded to achieve this, with clinics free to choose a larger practice payment, and shift away from fee-for-service funding.”

Support from other specialists was also imperative, suggested the report, calling on the government to set up a national secondary consultation scheme to enable GPs to easily and quickly get advice from non-GP specialists in public hospitals.

“Unlike now, doctors would not have to rely on their own personal networks to get advice, and there would be funding for both doctors’ time.”

Fix holes in the safety net

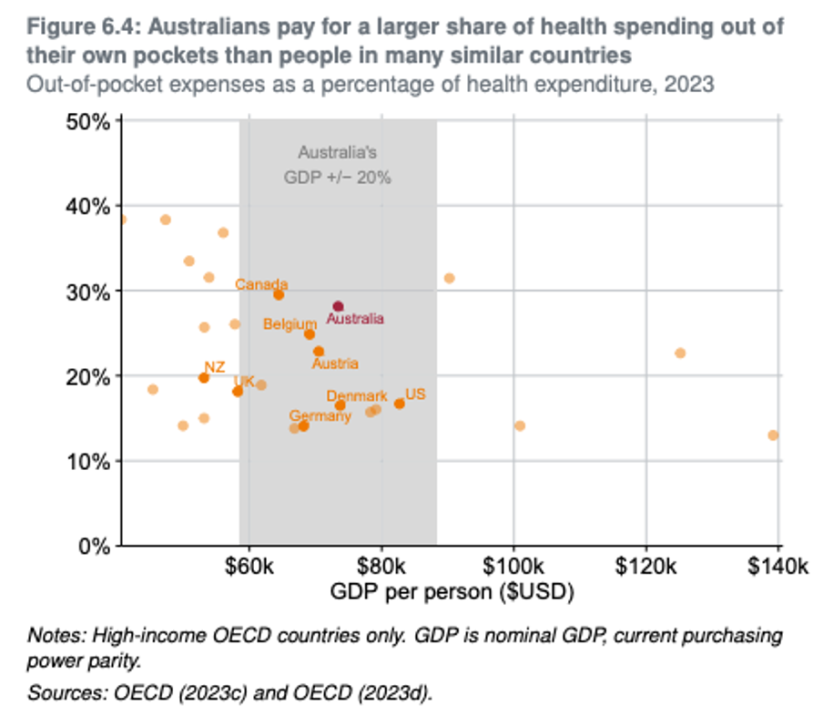

Australia’s out-of-pocket costs are higher than most OECD countries. We have the best health system overall, but the second worst for access to care.

A new approach to GP “deserts” was needed, said the Grattan.

“We know what works, thanks to years of experiments and trials, including local ‘single employer model’ initiatives in most states,” said the report.

“These approaches acknowledge that in persistently under-served areas, top-up subsidies through Medicare simply won’t work. Instead, tailored local efforts are needed to employ clinicians, ideally with federal and state governments working together to make the best use of scarce funding, infrastructure, and workforce.

“The federal government should set a minimum level of GP services per person. For regions that persistently fall below that level, funding should be available to fill the gap. It should be contingent on a contribution from the state government.

“The amount should be determined by the Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority. Plans for spending it should be agreed to by the Primary Health Network and the state, drawing from a range of broad options agreed to by the nation’s health ministers.”

Spend new dollars wisely

In order to fund prevention and fairer access, government will need to spend money upfront, said the report.

“Governments should systematically do three things in all the reforms: target the greatest need, pay for value, and increase accountability for impact.”

Quick wins

The institute recognised that those four reform areas would take time and be costly to fund. However, it also identified some low-hanging fruit:

- Introducing food regulations, such as mandatory labeling and advertising restrictions;

- A strategy to boost vaccination that includes setting targets, simplifying guidance, sending SMS reminders and providing a small amount of funding for tailored local promotion;

- Funding a national system that makes it easy for GPs to get advice from other specialists;

- Fixing the implementation of an existing policy that charges patients more for choosing less cost-effective PBS drugs, which could save hundreds of millions of dollars each year;

- Changing the way the government pays for pathology testing and negotiating so taxpayers share in the industry’s efficiency savings, which could save up to $175 million each year.

Read the full Orange Book here.