The lobby group’s annual public hospital report shows ‘horrifying’ increases in waiting times in ED for people in severe distress and the worst access in years.

The average wait time for a mental health bed in a public hospital emergency department has blown out to an average of seven hours, with one in 10 patients waiting over 23 hours to be admitted, according to a new report from the AMA.

The association’s 2024 Public hospital report card – mental health edition was released this morning and the news was grim.

“This is the third time we’ve released this report card and unfortunately, I have to tell you, it’s the worst year in terms of the access our patients with mental health needs have to our public hospitals,” said AMA president Dr Danielle McMullen.

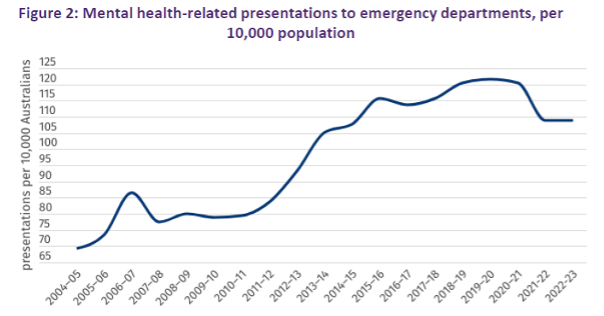

“We’re seeing more patients with mental health problems come into our emergency departments and they’re sicker than ever before.”

The big takeaways from the report are that:

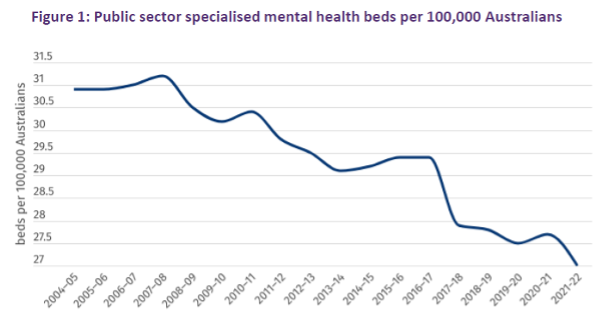

- In 2021–22, the latest year for which capacity data is available, Australia saw a reduction of 244 specialised mental health beds across the country, coinciding with an overall loss of two public hospitals providing mental health services;

- Australia has witnessed a long-term decline in the number of mental health beds available per person in the past 30 years – the latest figure of 27 beds per 100,000 Australians is the lowest per-person capacity figure on record;

- Since 2010–11, the number of Australians presenting to an ED with a mental illness triaged as “emergency” has more than doubled from 9 to 21 per 10,000 people, while the number of “urgent” presentations has grown from 37 to 57 per 10,000 people;

- In 2022–23, more than half (52%) of mental health-related presentations came via an emergency services vehicle, compared to 26% of all ED presentations;

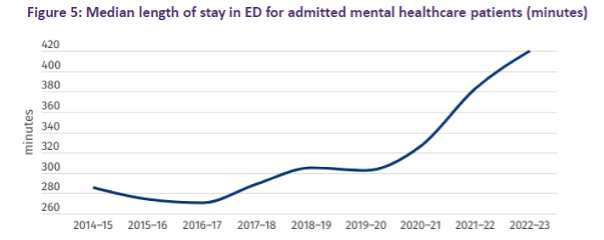

- Highly distressed patients suffering from severe mental health problems must wait, on average, seven hours in a crowded ED before they are admitted to hospital – the 90th percentile length of stay for mental health presentation admissions has risen to 1392 minutes, or more than 23 hours;

- In 2022–23, the average length of stay for mental health patients was 14.3 days, compared to 5.3 days for non-mental health admissions.

“Seven hours in a bright, crowded, noisy, loud emergency department is incredibly stressful for somebody who is frightened, who is anxious, who’s thoughts are distressing them,” said Dr Sarah Whitelaw, an emergency physician at the Royal Melbourne Hospital.

“The idea that 10% of these patients are waiting for more than 23 hours in this environment is absolutely horrifying.

Dr Whitelaw acknowledged that there is a commitment to more funding for public mental health beds in the next National Health Reform Agreement, as well as a rise in the cap on funding growth.

“But we have a situation where we have the lowest public hospital mental health capacity on record,” she said.

“We have a blowout in emergency department length of stay for these patients.

“We have increasing acuity and severity of our mental health needs of our population.

“We cannot wait. We need investment now.”

All levels of government were required to improve the situation, Dr McMullen said.

“We really do need all levels of government to take this seriously, [to] see what a state we’re in and where we’re headed, and make sure they’re working together to act now, improve our capacity and improve our ability to wrap around these vulnerable patients and provide them the care they need going forward.

“We need all governments to stop putting this in the too-hard basket,” she said.

The AMA’s report card presented a four-point plan to deal with “struggling, log-jammed hospitals”:

- Improve performance by reintroducing funding for performance improvement — for example, improvement in elective surgery and emergency department waiting times — to reverse the decline in public hospital performance;

- Expand capacity by giving public hospitals additional funding for extra beds (along with the staff) and supporting them to expand capacity to meet community demand, surge when required, improve treatment times, and put an end to ambulance ramping;

- Addressing demand for out-of-hospital alternatives by funding alternatives for out-of-hospital care, so those whose needs can be better met in the community can be treated outside hospital; programs that work with GPs to address avoidable admissions and readmissions should be prioritised;

- Increase funding and remove funding cap by increasing the federal government’s contribution for activity, allowing states and territories to reinvest the “freed-up” funds to improve performance, capacity and innovation; remove the artificial cap on funding growth that is shared between states and territories, so funding can meet community health needs based on realities on the ground.

Read the full report, including state-by-state breakdowns, here.