The $2m Boston Consulting Group PHN review is in danger of missing the elephant in the room: PHNs have never been run by DoHAC in the manner they were originally designed to be.

I once loved to rail at how eclectic and disorganised primary health networks are. Then I went to a PHN conference and became immediately suspicious that something was wrong.

Many of the people there were smart, competent and committed. That really threw me.

How could many of these organisations be so all over the place with what they were doing when these were largely a good group of competent and committed professionals?

If I’d done just a tiny bit of homework back then by identifying where PHNs sit in the Department of Health and Aged Care structure I conceivably would have been immediately most of the way to an answer.

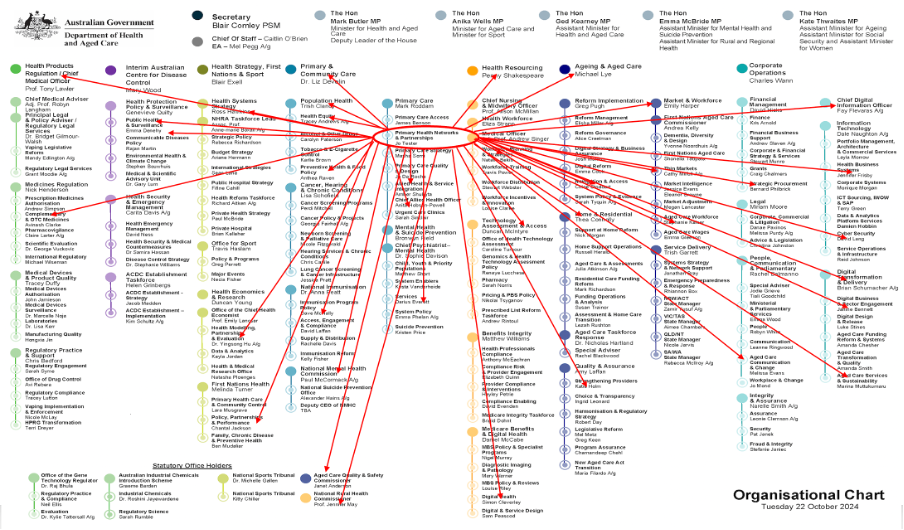

I’ve done that for everyone below. The red bits are me. The circle in the centre is where PHNs sit in this extraordinarily siloed and fragmented organisational chart. The arrows are all the related departments and agencies PHNs are more or less beholden to in executing what is effectively top-down DoHAC-driven strategy and programs.

I wonder if Liz Develin, the Deputy Secretary of Primary and Community Care, or one of her minders, have managed to do something like this for PHNs yet. Maybe that’s why there is review.

I wonder if Boston Consulting Group (BCG), who has been given $2 million to review PHNs, has done it.

It’s a pretty good way to start thinking about why PHNs might be so dysfunctional. The problem, of course, is that this graphic points to a problem outside of the PHNs themselves. It points to how DoHAC views and runs PHNs versus how DoHAC has always specified what they are meant to do and how they should run.

Imagine if you were thinking of becoming a PHN CEO and someone sent you this chart and said:

“Here’s where you fit and who you will need to be working with … don’t worry, each year someone is going to come up with something for you to do from the end points of one or more of those red arrows in, from what I can tell, a random way, and then from year-to-year give and then take away large blocks of time-limited funding to get the job done successfully, and then, you may, or may not, get measured as to how you performed based on this document developed for you by a high-end (and possibly now disgraced or bankrupt) consultant, prior to covid.”

I worked as a CEO in a global healthcare information behemoth (Reed Elsevier) in a far-flung country (Australia – which in the RE empire was the equivalent of one of those rebel outer system planets in a Star Wars episode) and while it got pretty crazy from year to year trying to interpret instructions from afar and work within a very complex matrix to utilise synergies from related service entities and companies, organisationally, it all sort of hung together in the end.

There was always a clear map of sorts, which started with a global strategy, and your place in it, and which went into a lot of detail on how you interacted with the rest of a super complex arrangement of global services and companies.

That does not look like what you’d get as a CEO of PHN if you think about the implications of the above structure chart.

DoHAC doesn’t treat PHNs as regional intelligence units on patient and provider needs, but as regional delivery units for ideas cooked up (not always poorly cooked up) from on high inside DoHAC from all the endpoints of those red arrows.

In one way PHNs seem to be a tactical deployment unit of DoHAC, where it’s very easy to get funds to what you think you want to fix in the regions quickly – which isn’t an entirely bad idea.

But if you read the department’s definition of PHNs here, what they are meant to be doing and how, you would immediately recognise that how DoHAC uses PHNs and how they describe them are almost two entirely different things.

DoHAC says PHNs mainly do the following:

“PHNs assess the needs of their community and commission health services so that people in their region can get coordinated health care where and when they need it.”

The problem is, they don’t, and it’s not their fault.

If they did, of course, you’d be thinking that these organisations are likely the critical pivot point around which the system can lever itself away from hospital-centric acute care to community-managed chronic care into the future.

In other words, PHNs could be the epicentre of healthcare system transformation – if we operated them the way we claim we do.

Ironically the same description of PHNs is provided for everyone who is considering putting in a submission to the $2 million BCG review here.

Which is very awkward.

How can you review a key organisational element of the system (apparently a key one) if you aren’t able to first look in the mirror and admit that in no way do you operate this element in the manner you are describing to everyone?

In this DoHAC universe of multi-coloured dots and circles PHNs have absolutely no agency or organisational connectivity to do what the Department says they should be doing.

So what are we paying $2 million to BCG to review here?

What could anyone at BSG do or say once they map the current directives and objectives of PHNs against how they sit operationally in this chart and how DoHAC actually runs them day to day?

If BCG is already at the one-on-one management interview stage of their consulting contract spend, and some of the management are bold enough to say things how they are, BSG is going to find themselves very quickly between a rock and hard place.

Their job is to review PHNs and say what needs fixing.

Now PHNs will have a lot of issues in how they are run, governed and performance managed without much doubt.

But if you haven’t been running PHNs the way you have specified they should be run, whose fault really is it that they aren’t delivering the right ROI to the system and tend to splay money in all sorts of weird and wonderful ways into projects that quickly go nowhere?

Can BCG tell the people who are paying them that before they reorganise PHNs in any way, they might want to ask themselves again what they really want PHNs to do, and how they really want them to operate?

The problem the DoHAC might have with such an enquiry is that the theory and idea of PHNs – on-the-ground regional needs analysers who identify specifically how to service a region more effectively and then commission services to the meet those identified needs on a priority basis, taking into account relevant national initiatives from DoHAC – is perfect.

But DoHAC isn’t running PHNs in that way. It’s running them to deliver programs nationally that they develop and want funded quickly and directly.

No organisation anywhere, even with the brightest minds, could fight the mess implicit in the structural positioning PHNs have been given within DoHAC and be successful, or indeed, be ever properly measured on performance.

In this scenario, most of the problems that BSG identifies downstream at the PHN will almost all have their origins upstream in DoHAC itself and how it is managing them.

DoHAC says to PHNs that they need to identify the needs of their particular region and commission services to meet those needs.

Then DoHAC blithely sends down what they interpret the needs of each PHN are based on their own needs – programs they have developed within the department as a part of the department’s broader strategic and functional wants and needs.

In other words, they ignore the regionally based needs intelligence they have asked PHNs to gather almost entirely to fulfill broader strategic objectives that have been identified in their own departmental programs.

That DoHAC largely ignores the regional intelligence component of what PHNs are supposed to do is made obvious in the dynamic that nearly all the major programs that PHNs are asked to deliver are provided to all 31 PHNs by DoHAC year-to-year with very little, if any, fidelity added for delivery between each region.

In doing this DoHAC largely ignores that PHNs are regional organisations by design, the main purpose of the design being that if they are local they can understand and translate important differences in needs between different populations of patients and providers in each region.

Obviously, between a remote and an urban PHN catchment, there are vastly different patient and healthcare provider needs.

So DoHAC has round-peg ideas, and PHNs somehow have to fit a series of them into what often end up being local regional square holes. Holes that would have been identified in the original PHN needs analysis as being square, and ignored.

This dynamic is known as reverse commissioning: you ask an entity to identify needs with a view to commissioning services to meet those needs, but you then send them your needs and demand that they commission to your needs, not the ones they have identified.

Some specific examples of operational deployment of initiatives directed to PHNs by DoHAC in the last couple of years might help to illustrate this point.

Urgent care clinics (UCCs) are a high-profile example.

Unsurprisingly, UCC locations have largely been determined at the federal level, and dare it be said, sometimes politics plays a part in location.

PHNs are then directed to work it out from there and get given the work of determining which local provider will get the pre-determined gig.

That’s reverse commissioning.

Virtual aged care initiatives are another example.

Last year DoHAC provided all PHNs across the country with a lot of commissioning funding to go forth and engage with their local aged care facilities to bolster their ability to connect virtually much more effectively to local healthcare provider resources. That’s actually a good idea.

But this was multimillion-dollar funding directive to all PHNs without any real adjustments made between the 31 different PHN regions.

We want aged care more connected everyone. Go forth and commission some providers to do something!

What ended up happening was an eclectic mix of solutions by region and PHN, a good proportion of which had very little to do specifically with local needs, and most of which had no continuity with plans being developed and deployed in parallel by the many other units (other coloured dots with circles) within the department deploying aged care strategy.

Some PHNs simply asked their local aged care providers what they wanted to do with the money, gave them some, presumably thinking this is solving a problem locally, and unsurprisingly, many aged care facilities did really stupid things with the money.

No one has audited this program, by the way.

Interestingly, and this is why we suspect that PHNs are definitely potentially very important for more efficient running of the system, some PHNs organised themselves very cleverly on a regional basis – and commissioned technology providers to put really cool new virtual care technology into a surprising number of aged care facilities across the country.

WAPHA managed to place such a virtual care kit into every public aged care home in the state.

But the funding for this initiative, like so much PHN funding, was pretty much one off.

This is how a lot of PHN funding seems to go. There’s not a lot of thought to tying the funding to sustainable objectives or connecting and aligning the initiatives with different government units, like aged care or mental health.

There wasn’t any thinking about who would train people in those facilities to use the new technology, what would happen when the first investment tranche of money ran out or who might run ROI analysis for the aged care providers on their new technology so they might be persuaded to keep investing past the initial one-off investment.

Was there any cross-divisional alert to the various aged care units in DoHAC to coordinate with what some PHNs had managed to do?

This all very likely means that the chance of the money leading to sustainable changes in aged care connectivity and effectiveness are very low. The funding, like PHNs, has not been intelligently connected to broader healthcare strategy and funding.

PHNs have not been intelligently connected or empowered either (see structure chart).

Whose fault would the failure of this aged care program be, do you think, BCG? Because it doesn’t look like the blame should be laid at the feet of the PHNs given the context in which they were given the money.

Another good example of this sort of one-off thought-bubble top-down reverse commissioning to PHNs on the part of DoHAC emerged this week around the funding of the development of general practice resources in what is termed “thin general practice markets”.

The idea behind “thin markets” is perfectly sensible: identify where you need GP resources but the commercial model doesn’t stack up (remember, most GP services are private small businesses) so provide anyone local who is interested with enough funding to make the idea of starting a practice in such a market commercially viable (and presumably somehow sustainable).

DoHAC found $33 million to fund this program.

But, fairly obviously, this was not a program that had its origins in the needs analysis of any of our 31 PHNs.

How do we know that?

We are 18 months in and only two PHNs have applied for and received money for the program, and with only six months to go because the grant program expires, there is $28 million left in the kitty.

Read our story on this here because Northern Queensland PHN got over $3.5 million of the $4 million that has been deployed but neither they nor DoHAC will tell us what they are actually going to spend it on, saying it’s all “commercial in confidence” (who are they competing with we wonder)

This all feels crazy.

There would not be a rural town west of the great divide on the eastern seaboard of Australia where there isn’t a high level of need to help prop up local GP services.

If PHNs were really involved in this program from the ground up identifying local needs, communicating that to DoHAC and then being given the go-ahead to commission services to that need, that money would have been spent, and probably reasonably well.

Another problem that BCG should have a very close look at and determine if PHNs are to blame or not is just how much money PHNs spend each year on mental health and how it looks poorly spent but no one knows because no one measures PHNs. DoHAC is supposed to do it but the measurement framework is a complete mess and the last time they did it was 2019.

Of the more than $1.2 billion in grant funding PHNs get each year, nearly $700 million of it (maybe more now) is directed at PHNs building out and deploying mental health programs.

Which sort of makes PHNs Primary Mental Health Networks (PMHNs) more than anything else (another thing BCG should question – how do PHNs get anything done when mental health is their primary directive?)

Until recently nearly all of this money was being deployed outside of local general practice services – often via unproven mental health software platforms and via DoHAC directed contracts with organisations such as headspace.

This money is also handed out to PHNs pretty much on a reverse commissioning basis. A lot of it is tied to the PHN working with local Head to Health groups (a separately run DoHAC federal mental health initiative).

PHNs are supposed to be commissioning experts (some are getting good at it) but how is it commissioning for local services when the funding is tied in this manner?

PHNs look like they are just the regional service organisers for what is effectively a federally run set of mental health initiatives. That dynamic seems to have a lot in common with how DoHAC has directed them to get UCCs up and running in their region.

When you consider that the vast majority of our complex mental health is dealt with by a significantly under-resourced and stressed general practice network, and for years this money has been deployed almost entirely outside this network, largely under the direction of DoHAC, who would BCG blame for how ineffective this spend has probably been so far?

Obviously, there are some national programs that make sense to deploy without much if any regional fine tuning. DoHAC is doing some of that for sure, and probably mental health is one issue that needs national direction. But ignoring specific regional needs in the manner that DoHAC has directed in spending all this money so far?

Some questions for BCG in this review might be:

- Does DoHAC fundamentally not understand how commissioning of healthcare system needs works?

- If DoHAC really wants to understand regional needs and deploy to that understanding, do they need to start running PHNs in the manner that they say they already run them but don’t?

- Is DoHAC reverse commissioning and if so is that working for the healthcare system?

- Should DoHAC reorganise internally in order to connect PHNs properly with all the many units that PHNs end up trying to deliver services for as a result of the reverse commissioning that is going on?

- Do the senior management of DoHAC and many of their unit managers need to go overseas and learn how commissioning works in countries that operate a regional commissioning model properly?

- Are many of the immediate problems we see in PHNs really a problem with how its master, DoHAC, operates them?

PHNs are far from perfect. They need a lot of work around things like governance and performance measurement.

But they are a great idea proven overseas.

So, before we spend $2 million putting the spotlight on them as a problem, do we need to be honest with ourselves as to what they really are there for and how we really mean to run them?

In similar regional commissioning health care groups run in functioning and fast evolving overseas healthcare systems such as Canada, the idea of PHNs works really well.

Maybe before we spend $2 million blaming them for waste and then reorganising them, we should first consider running PHNs the way they were designed to be run.

If you managed to read this far and think it maybe didn’t make a lot of sense, but would like to contribute your ideas to the BCG PHN review, click here.

Note: PHNs as regional analysers of system needs and commissioning units will be one of a series of key issues to be discussed at Health Services Daily’s Towards One Healthcare System Summit and Workshop being run in Canberra next year on 17 and 18 June. You can see a program and early speaker list HERE and get a great pre-Christmas discount on your ticket HERE.