There are more than three billion reasons to advocate for structural change in the PHI industry rather than the lazy call for a mandatory payout ratio.

Having spent the past year roundly criticising the antiquated business models and strategic missteps of many of the Australian private hospital operators, I thought it was long overdue to alienate many of the Australian private health insurers, albeit for different reasons.

While the private hospitals, peak bodies, and their minions are pushing government to mandate minimum payout ratios for PHIs, this does nothing to enhance efficiency in the sector and will inevitably lead to further vertical integration as a mechanism for PHIs to circumvent such a blunt instrument.

Instead, there is a simpler option that would release billions of dollars into the sector to be applied to better coverage, lower premiums, and more revenue for providers.

Sounds too good to be true?

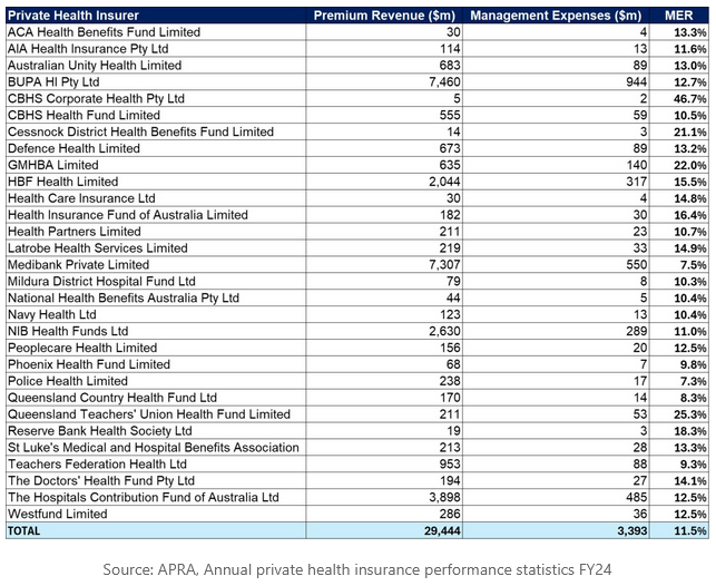

In FY24, there were 30 PHIs operating in Australia. Collectively they generated $29.44 billion in premium revenue (excluding investment and other income). In aggregate, they spent $3.39 billion on management expenses (their administration and selling costs) which represents an industry average management expense ratio (management expenses divided by premium revenue) or MER of 11.5%. However, there is significant variation by fund around this average as per the table below:

Medibank and Police Health are the standouts with an MER of 7.5% and 7.3% respectively. If these two PHIs, at opposite ends of the scale spectrum, can operate effectively at this MER then there’s no logical reason why the rest of the industry can’t.

Yet it’s not difficult to see the laggards in the table above. To put it simply, if the entire PHI industry operated at Medibank’s MER of 7.5%, total industry management expenses in FY24 would have been $2.21 billion rather than the $3.39 billion that was actually spent, representing a saving of $1.18 billion per annum.

Given that the federal government controls premium increases, it simply wouldn’t allow such efficiency gain to be trousered by the PHIs in the form of higher profits. The savings would need to be applied by the PHIs to some combination of better coverage, lower premiums, and more revenue for providers (all of which represent upside for providers either directly or indirectly).

The regulatory instrument the government should therefore consider is a maximum MER rather than a minimum payout ratio as this would force efficiency in the sector. It would also inevitably lead to consolidation in the PHI sector which I’d suggest is a good thing as there is little rationale, beyond sentimentality, for the current number of industry participants (cue the howls of protest).

The PHI industry is highly homogeneous in terms of product and pricing.

This is entirely by design as government mandates product categorisation and coverage (basic, bronze, silver, gold) and the key tenants of the system, such as community rating, risk equalisation, no denial of cover for pre-existing conditions, and second tier, mean that pricing and network coverage are also largely indistinguishable.

Related

A fund with the healthiest membership base in the nation would barely be able to undercut its competitors on price as the vast majority of its product costs would be contribution to the risk equalisation pool.

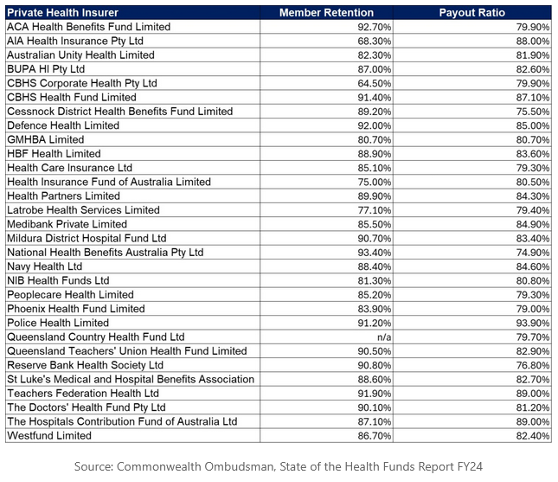

The often used argument that smaller or not-for-profit PHIs provide more value to consumers in the form of better service, lower premiums, higher payout ratios, or lower out of pocket costs is simply not borne out by the evidence:

Even if some PHIs have a higher payout ratio than others, this does not mean that their members are getting more value.

If those PHIs simply pay more for the same treatment as their competitors (i.e. they purchase services relatively inefficiently on behalf of their members) then they will have a higher payout ratio without providing an iota of additional value.

So how many PHIs would be needed to ensure robust competition and avoid oligopoly?

I suspect five would be sufficient (regardless of whether they’re for-profit or non-for-profit). The private hospital sector may disagree, though in effect this would make little difference to their bargaining power given that smaller funds already purchase via a buying group.

Moreover, if 30 PHIs became five, I’d also expect that the management expenses of the 25 PHIs that are subsumed could be absorbed by the five remaining without lifting their current management expenses by leveraging their significant investments in systems and infrastructure across a larger revenue and member base (albeit there would be one-off merger integration and transaction costs).

Thus, the $1.19 billion in prospective management expense savings should be materially higher. For example, if the top five current PHIs by revenue operated at an MER of 7.5% then their aggregate management expenses would have totalled $1.76 billion in FY24, some $1.64 billion less than the actual FY24 industry total.

Assuming that the rest of the market could be absorbed at nil uplift to management expenses (excluding one-off costs), this would imply an industry MER of 6.0% ($1.76 billion management expenses divided by $29.44 billion of premium revenue).

Industry consolidation would likely have additional benefits.

In the lead-up to covid, the PHI sector was in a world of pain, with membership for hospital cover in absolute decline (not to mention accelerating downgrading of policies) as consumers were increasingly disaffected by premium growth and out-of-pocket charges.

Concurrently, the public hospital system, with whom PHI competes, had largely completed a phase of new hospital building with single rooms and ensuites undercutting one of the key drivers for purchasing PHI.

Around a third of the 30+ PHIs in the market at the time were making an underwriting loss, propped up only by returns on investment income. Were it not for covid, industry consolidation would have occurred by now.

While public system performance is unlikely to recover anytime soon, the inflationary pressures that drove underwriting losses pre-covid are nonetheless returning, as demonstrated by the recent round of premium increases.

I have no doubt that I will be lambasted for suggesting that the value proposition of all PHIs is essentially undifferentiated and many will point to the great service provided by smaller funds and the work that they perform in their respective communities.

They would further argue that constraining the market to a limited number of large PHIs would impede innovation and choice in the sector.

The reality is that most of the sector innovation to date has emanated from the large funds and that PHI is, by design, a utility. Like any utility, services should be provided as efficiently as possible. If providers are seeking higher reimbursement and more volume to address their economic fundamentals, then there’s more than a billion reasons to advocate for structural change in the PHI industry rather than the lazy call for a mandatory payout ratio.

Marc Miller was formerly chief strategy officer for Medibank for almost 13 years until September 2022. He is currently managing director of Healthcare Systems Advisory in the UK.

This article was first published on LinkedIn. Read the original article here.