Sometimes delivering more efficient care isn’t as wicked or as complex as we think it must be. But you have to join the dots.

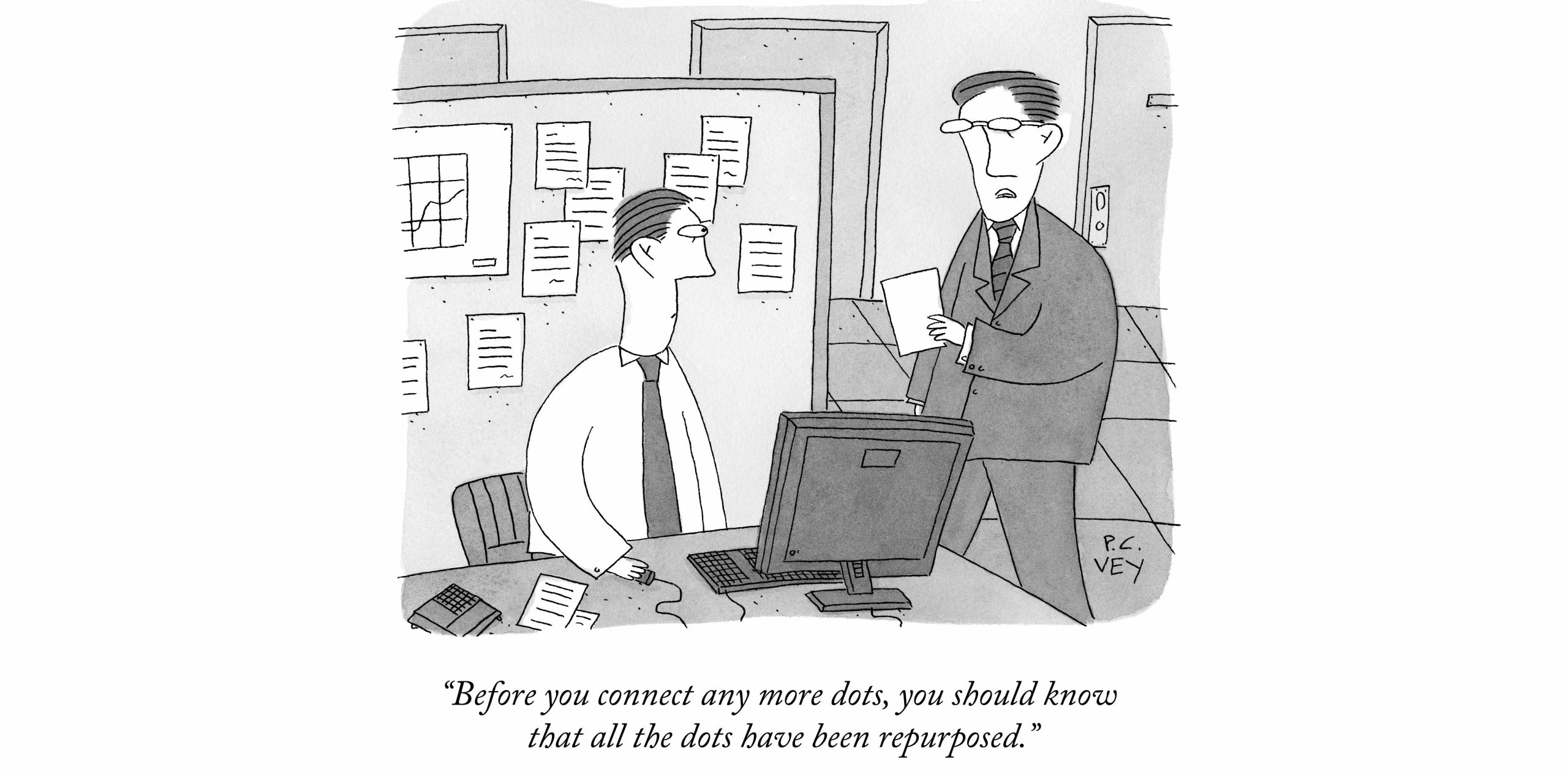

Two related stories came across my desk this week separately and no amount of reading and re-reading the background on each got me anywhere near reconciling how the Department of Health and Aged Care was ultimately the funding body behind each story, because the two stories read together don’t make sense.

One was a story about a wayward listed small cap health tech group called Visionflex (initially 1st Group), that somehow turned around what looked like an inevitably bad ending into a robust growing business. It did it via winning and executing contracts with at least 15 PHNs to install sophisticated virtual care hardware and software into nearly 20% of all of our installed base of residential aged care homes in Australia.

As a result, most of these RACHs – 180 in WA, which is nearly every aged care home in that state – now have the ability to do sophisticated telehealth sessions between their staff and residents and any nominated external provider willing to get on the other end of the virtual care gear – be it GP, nurse, allied care or other.

That sounds like magic when you think about just how badly disconnected our aged care facilities are from the rest of the system and all the antiquated clinical management software they use, if they use any at all.

If anyone had asked me how do I get this sort of kit into over 500 aged care homes across the country in less than 18 months I would not have known where to start, and I would have thought, “that’s going to cost way too much, where would that money come from”.

The problem for Visionflex, the PHNs involved and those 500 aged care facilities now is, who trains the people in the aged care facilities to use this neat new kit? How do they establish a good set of external providers who can be on the other end of the kit when required? And, probably, who keeps track of the numbers so that someone has data on what works and what doesn’t between each of the installations?

That’s a pretty big problem but Visionflex is gearing up as well as it can to do it all it can to make it happen because, as things go, if no one starts using the kit and there isn’t a compelling ROI on it being in there, the project may be dead in the water within a year or so and all that PHN and DoHAC money will have been wasted.

As typically happens with PHN funding, the way the PHNs dealt with the money they got to do this work was seriously eclectic across the regions. But some seemed to have gotten their act together by centralising coordination and resourcing. WA, in particular, is an amazing result so far.

But the funding is only really to get the kit on-site, not to identify and train staff inside a facility to use the kit properly, make sure relevant outside providers are aware of the capability of each facility and ensure that important data on use is captured so everyone can learn and adapt as they go.

The amazing aspect of this initiative, which has been funded for at least a few million across the country ultimately by DoHAC, is just how many aged care centres our now suddenly equipped to do virtual care.

The downside is that, as often happens with PHN projects, there isn’t a lot of continuity of thinking about what is required for a project to make it sustainable.

The other problem for a company like Visionflex is that PHNs chop and change what they fund very quickly, often at the behest of their ultimate master, the DoHAC.

Likely any funding for this project will be between 1-3 years at best and after that if an aged care facility doesn’t work out how to use the kit, don’t bother trying, or don’t see a return on continuing to invest themselves – which will always be hard because they don’t have a lot of incentive directing them this way – then what began as a good idea and an amazing start will wither and die.

Now to the related second story that we are finding hard to reconcile.

Just over a week ago the aged care part of DoHAC released a $30m tender for over three years “to support the development and testing of a framework for the delivery of virtual nursing support in aged care”. That story is here.

The wily reader might immediately see how these two stories are connected and wonder what the connection is between one part of DoHAC funding the PHNs to help their local aged care homes to do virtual care, and the other putting out this tender to work out how and if they can use virtual care technology to help solve their nursing workforce problem at some sort of scale across the nation’s aged care sector.

If the two initiatives were a Venn diagram you’d be seeing a lot of overlap.

Spoiler alert, there doesn’t appear to be any connection.

Worse, based on a reading of the detailed tender document for the virtual aged care nursing tender, you’d have to suspect that the people putting out the tender might not even have any idea of what the PHNs and a small local health tech company have already achieved in terms of installed virtual care capability base that is immediately relevant to the $30 million tender.

It feels like it might be even worse than this in some respects. Of course it does.

According to the tender the $30 million will only be used on about 30 selected aged care homes, over a period of three years.

That’s $1 million per aged care home – not that the aged care home will see any of this money (the vendors who win the tender will) – to provide some sort of proof of concept and possible adjustment to existing ideas developed by the aged care experts at DoHAC, for understanding if we can somehow use virtual care in lieu of being able to have an actual nurse in a home 24/7.

According to the tender the Department, in consultation with the Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission, will select a sample of just 30 residential aged care homes to participate in the project. The selected homes will be ones which experience at least a gap of eight hours per day of registered nurse on-site availability.

Certainly, some good people would have been thinking long and hard about the potential cost of doing what is effectively a pilot and came up with the $30 million number – work nobody is privy too – but it’s hard to see what you’d spend $1 million per facility on over a period of three years to prove this stuff out.

All the while, we already have at least 500 aged care homes with the technology in place, and presumably some are trying to work out their own training and how to get local or even well-established national virtual care providers to man the other end of the line when they need it, now.

The tender says that if an RACH participates it will get:

- access to virtual nursing services;

- training and education measures for staff on using virtual nursing, including training on applicable software and equipment;

- upgrades to, or enhancement of, available technology to support delivery of virtual nursing services;

- engagement with other participating providers, for example through a Community of Practice; and

- relevant findings from the evaluation that may contribute to future service delivery.

A vendor winning the tender is required to use the draft Virtual Nursing in Aged Care Framework developed by DoHAC to implement and operate their virtual nursing services solution.

So, what happens to those 500 facilities already starting to operate outside these parameters?

What happens, for instance, if one or many of these 500 get their implementation working with an existing virtual care provider, for example Healthdirect, which not only already has a free nursing triage service but now a rapidly building virtual care workforce including not just nurses but GPs?

Does the right hand of DoHAC working inside an aged care cubicle somewhere realise what the left hand, working with PHNs in another cubicle, has already done?

If they did, you’d have to wonder if $30 million to test only 30 facilities over three years might end up being some serious overkill.

If you look at the objectives of the $30 million tender project you can’t really see anything that wouldn’t be in the objectives of the PHN push:

- Contribute to residents having access to quality clinical care 24/7 when and where they need it;

- Support the aged care workforce to provide high-quality care, for example through providing access to additional clinical expertise; and

- Provide a high-quality and sustainable adjunct to face-to-face care during periods of workforce shortage.

The irony here might be that the PHN initiative has the potential to deliver all those objectives at scale, not just as a 30-facility pilot, much less expensively, and much quicker.

But all the good work the PHNs have so far managed to achieve could easily just break down now and be wasted without a little more funding to push all those centres with installed technology to identify and train staff to work the equipment and to make sure that there are virtual providers at the other end of the line.

That money looks like it is going to be tied up in what looks like a completely separate project, which hasn’t even started yet, and which is only looking for proof of concept, using 30 facilities.

Here’s another possible flaw in what is unfolding.

The following is a list of the services required of a successful tenderer on the $30 million project:

- capability and/or experience in establishing and/or upgrading interoperable/integrated technology to support clinical care in RACHs, including ability to securely access electronic medical records;

- experience in delivering training and education to on-site RACH staff on how to support older people living in residential aged care requiring the virtual nursing service;

- experience in supporting the delivery of culturally appropriate care via virtual technology (i.e., video telehealth);

- capability/experience in the provision of real-time clinical services (with a focus on RNs with aged care competencies), and supporting continued quality of care and services (including continuity of care for residents);

- experience in the delivery of culturally safe, trauma-aware, and healing-informed services for vulnerable populations (such as First Nations peoples);

- capacity/capability to comply with relevant legislation, policies, and/or standards in delivering clinical care in RACHs via online mechanisms.

When I first read this list one particular organisation came immediately to mind: Healthdirect.

Healthdirect already does most of this in its current day-to-day work and is probably the single most informed group around data on how various aspects of the community use and misuse virtual care to connect to the provider community.

Healthdirect is also funded by the states and the Commonwealth to do work that involves facilitating virtual care in aged care facilities.

Is it way too simplistic to suggest that Healthdirect is an existing and obvious party that could do this work?

You probably wouldn’t have to fork out $30 million for them to do it, especially given that 500 facilities around the country already have new virtual care gear ready to go. And you could probably do it in a lot more than 30 carefully selected centres – presumably a lot of the 500 with the kit want to start using it the best way they can as soon as they can.

Maybe it is too simplistic.

But if you look at the PHN initiative, the most pressing and important next step, largely unfunded, is training and education of the facility staff on the tech they now have.

The tender actually states the following with respect to that element of the project:

“The Successful Supplier/s will be responsible for providing access to initial and ongoing training to all applicable staff on the use of virtual nursing, including the practical use of technology and the requirements for delivering care via technology. This may include provision of training to direct care staff (e.g., nurses, assistants in nursing, personal care workers, allied health professionals, or Aboriginal Health Workers), management staff, or agency staff depending on the unique needs of the RACH. Training may be delivered through a sub-contracted organisation.”

There are a lot of big private groups who will likely be eyeing off this tender and the $30 million offer. They will put in impressive bids to spend every cent of the money. Groups like Medibank, Bupa, Aspen Medical and more.

But none of those groups have what Healthdirect already has – it can do the nursing part of the tender now and throw in triage for any situation a virtual nurse might assess as a problem with a resident.

In other words, Healthdirect has vastly expanded virtual care management capability and is connected to just about everyone who can help. It can assess and connect an aged care centre to a multitude of other virtual provider services depending on need on the spot, or, it can get someone to hospital immediately if needed.

Maybe Healthdirect will end up being one of the tendering organisations for this $30 million pilot?

It would be strange if they weren’t, and they didn’t end up playing some role here.

Between both these initiatives – one from the PHN part and one from the aged care part of DoHAC – there is certainly a lot of great intention and ambition in this $30 million tender.

But not a lot of coordination, and perhaps, not a ton of commonsense either.